Why Tom Cruise is Hollywood Jesus, but Failed to Cast AI as Satan

The latest movies about AI don't explain much about our tech future, but there are important lessons to be learned.

In the last month, Hollywood released two sweeping commentaries on artificial intelligence, shepherded into the global consciousness via Apple TV’s Mountainhead, directed by Jesse Armstrong, the creator of the hit HBO series Succession, and Mission: Impossible - The Final Reckoning, directed by frequent Tom Cruise collaborator Christopher McQuarrie.

These auteurs know how to tell a story. So surely they could craft fascinating narratives around the most talked-about topic of our time, AI, and its potential to disrupt nearly every facet of human existence. Right? Well…maybe. Let’s start with Mountainhead. Armstrong spent four seasons skewering the modern media industry, revealing its many absurdities through a brilliant cast of characters, each more neurotically monstrous than the next. The scathing David Mametian verbal lacerations and ego defenestrations were so good that the tale of media empire served as mere window dressing.

The same holds true for Mountainhead and AI, as four tech moguls meet for an annual private poker game that turns into a congress on the future of humanity as generative AI (specifically, realistic video) throws the world into chaos by stoking civil unrest and toppling governments. Most of the film’s runtime is spent dishing bespoke deep cut insults and half-smile jousting over who has the biggest wallet.

In the end (yep, Spoiler Alert), the AI threat isn’t addressed with any real finality, but a literal life and death business deal is sealed, and our characters exit the stage. Mountainhead is as much about AI and tech as Succession was about what really happens in the media business. And that would be fine if the concerns around AI were as ephemeral as which mega media merger might soon dictate who you’ll have to pay for news and your favorite streaming TV series. But the AI stakes are much bigger, and the only crowd Armstrong really satisfies here are the “tech bro” naysayers who giggle with acerbic glee every time a billionaire puts his social media foot in his mouth over something outside his narrow tech business lane.

Final Reckoning is a different story. It hinges its entire story on the threat of an all-powerful AI that, for some reason, is threatening to nuke the entire planet so that a small cohort of its human acolytes can rebuild the planet under its new “Anti-God” (they actually call it that in the film) dictates. And that ecclesiastical-ish Anti-God moniker for what the film generally refers to as The Entity is the loud pulsing clue that McQuarrie and Cruise essentially “vibe coded” the story for a film that in most hands would be treated as science fiction, adhering to some form of sci-fi movie logic. There is no real logic here. AI is effectively slotted into the same threat role as nuclear weapons, while paying only passing attention to the notion that The Entity is a new self-aware being on the planet.

The Failure of Tom’s Impossible AI Mission

The original Mission: Impossible series, circa 1966, as with Cruise’s franchise, always started with an incredibly clever mechanism delivering the “impossible mission” message to the team leader. Then the same theme song would kick in, and at some point in the show, one of the team members would reveal a brilliant mask disguise as part of the mission. These three tropes, according to McQuarrie, are Cruise’s only rules for the franchise. They work. I love them. Therefore, I don’t relish this dissection of the film, but by injecting AI as a hook into the story, I, for the first time, was compelled to go back and reverse-engineer the plot in an attempt to understand a number of confusing choices.

Cruise’s Mission: Impossible films have almost always been narratively labyrinthine, instantly making the films rewatchable, if only because you still don’t understand what you saw. However, Cruise applied the formula to the wrong topic (AI) this time, despite his past and present box office success.

Many years ago, master director Alfred Hitchcock popularized the term “MacGuffin,” which is basically a plot device (a jewel, a rare manuscript) that is presented as very important early in the script, but ultimately isn’t centrally meaningful to the overall story. Cruise’s Mission: Impossible films have often used this MacGuffin technique to great effect to pull a story along. But AI, and a potentially self-aware AI at that, is no MacGuffin. So why, Tom, why?

Well, in 2023, during the SAG-AFTRA strike, production paused on Final Reckoning, and McQuarrie offered some insight into his production process with Cruise. “When it came time to start writing this movie, we were talking about what the global threat was. I said to Tom, it's the notion of information technology, of algorithms… It was now something you could feel in the zeitgeist that was permeating people's lives, and it was a thing people were aware of,” said McQuarrie, on the Script Apart podcast.

“To be really clear, the [AI] entity didn't exist as The Entity when the story began,” said McQuarrie. “Tom kept saying, ‘I just feel this other presence in the story. I feel that Gabriel [the human villain Cruise spends most of his time fighting in the film] is part of something, that he's not the main villain, that there is something behind Gabriel, and I don't know what it is.’ And [Cruise] kept referring to this phantom. And he just felt like we needed this other presence.”

And that is how AI became the villain that isn’t really a villain in Final Reckoning. Not as a profound treatise on what AI may soon mean to humanity. Not even as a well-crafted sci-fi anecdote of where AI could go. No. In Final Reckoning, AI was originally conceived as a literal person. A phantom operator (think Christoph Waltz as Blofeld in James Bond’s Spectre, 2015) from the character’s past. That was the plan…until they decided to shoehorn what may be the most consequential technology in human history into the role of a neutered supervillain shadow. The AI in Final Reckoning is nothing more than a MacGuffin, loosely crafted to merely get us to the end of the film.

They decided to shoehorn what may be the most consequential technology in human history into the role of a neutered supervillain shadow. The AI in “Final Reckoning” is nothing more than a MacGuffin, loosely crafted to merely get us to the end of the film.

Maybe the unusual sloppiness from this winning team is, in addition to inspired vibe scripting, partially the result of the difficulties that plagued the production for years. Production on the first part, Dead Reckoning, began in February 2020 and was almost immediately forced to stop amid pandemic lockdowns, making filming nearly as difficult as an impossible mission force caper. Not long after, production was again halted due to the pandemic. And then, when production on Final Reckoning started, the SAG-AFTRA strike posed yet another hurdle, forcing production to stop for a long stretch. By the time these movies were done, Cruise and McQuarrie probably felt that just getting them done, and done well, was an incredible achievement. And they would be right.

But a lot has changed in the last few years during their production hell, and AI can no longer be seriously relegated to a meaningless plot device. AI in the final (?) Mission: Impossible film is not just a system error in the franchise; it’s a failure to stick the landing in an otherwise believable eight-part cinematic universe.

The Triumph: There is no substitute for working near death

The irony of Final Reckoning’s AI fail is that by sticking to his old school “only real stunts” process, Cruise ultimately demonstrates why AI film isn’t necessarily doomsday for Hollywood storytellers. Tom Cruise is crazy (in a good way). That was my primary takeaway after watching Final Reckoning. His underwater and aerial stunt work, all done, as usual, by the star, continues to push the boundaries of risky reality in service of fantastical fiction.

Still, Cruise, McQuarrie, and every other actor, cinematographer, grip, sound technician, costumer, makeup artist, and food worker, if they are smart, are, like many in Hollywood, closely watching the developments in AI as it relates to filmmaking in particular.

When Google unveiled Veo 3 at its Google I/O event on May 20, you could almost hear the shivers run through Hollywood’s collective spine. The near-flawless generation of nonexistent humans acting and speaking in a wide array of situations stunned even many in the AI space. In short order, a number of users began posting examples of what the tool is capable of. Fake documentaries, advertisements, and short movie scenes. In many cases, the video outputs are so realistic that one ironic meme on social media has people posting real videos of real human beings and claiming that it’s Veo 3-generated—a kind of backhanded compliment to just how well the tool performs.

Predictably, this has reignited the anxiety-ridden internet discussions among traditional filmmakers, both established and aspiring, regarding the future of the craft. What does it matter that Cruise actually flew his own airplane to execute his death-defying stunts if someone with a few thousand dollars in Google credits can generate their own human protagonist executing the same stunts high above a virtual Grand Canyon?

The Truth About Reality

Despite Google’s industry-shaking announcement, OpenAI remains one of the most talked-about names in generative AI. That’s why when the late Steve Jobs’ partner Jony Ive emerged from relative obscurity many months ago amid rumors that he was working on “something” with OpenAI CEO Sam Altman, there was quite a bit of buzz around what the AI company might be incubating with the design master responsible for the iPhone, iMac, iPod, Apple Watch, and MacBook.

Like Jobs, Altman has cultivated a flair for the dramatic, often accented by meaningful timing. Fittingly, one day after Google’s Veo 3 reveal, Altman took over the AI news stream by formally announcing the $6.5 billion acquisition of Ive’s company io, effectively obscuring the fact that OpenAI’s Sora had just been outclassed. Just 24 hours after Google’s seeming game changer, Altman and Ive reset the conversation around what an OpenAI mobile device might look like. Now the leading question was whether the forthcoming device’s Apple-designer DNA might allow the AI startup to supplant the mighty iPhone, whose “Apple Intelligence” software tool has become something of a punchline among AI experts and end-users alike.

But reading between the lines, there’s a broader point to be made that speaks to the concerns from the filmmaking community. Along with OpenAI’s warm and fuzzy blog post about the Ive acquisition, the company posted a video showing the two meeting at a restaurant in San Francisco. The setting: Cafe Zoetrope, an eatery established by legendary filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola (The Godfather, Apocalypse Now) on the ground floor of his American Zoetrope film production building. Ironic foreshadowing or intentional thematic juxtaposition? Either way, the parallels tickling at what was and what will be feel momentous.

After settling in, the two talk about family, friendships, and the values they share. They each speak to an off-screen interviewer, as well as to one another. The story they are telling is one of human connection.

And that is the glimmer of hope that should inform storytellers everywhere regarding what AI can and cannot do.

Instead of employing Sora to tell their founder story, they opted to get in front of the camera themselves. Instead of using avatar Altman and Ive in a nonexistent cafe, they put humans in a real place that has real meaning, in a real city that they each spoke lovingly about. The subtext was clear: When we want you to really understand how important our message is, we will give it to you directly, with no AI intermediary.

Similarly, when Sundar Pichai took the wraps off Veo 3, he did so via his own personage, connecting with a live audience, rather than through the tool that almost certainly could have delivered the same scripted remarks using realistic AI video.

Am I hinting that realistic AI video is dead on arrival because people prefer a human connection? Not even close. The truth is more nuanced.

What’s Next?

We will likely soon experience a subtle splintering of viewing habits and visual production between AI video and “real” video. But that split won’t always be absolute AI or purely real, hybrid productions that mix the two are already becoming common. Some films and videos will be entirely AI, and some films and videos will be entirely real-world video. Between these two extremes, which will both have their own audiences, there will be a grey area of movie and video production that defies strict categorization and compels viewers to focus more on the story being told.

An example of this can be found in George Miller’s 2024 film Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga. In many of the debates around AI filmmaking, I’ve rarely heard anyone mention the AI used in the film to face match Anya Taylor-Joy to the younger version of her character, played by Alysa Browne. The AI work was handled by Metaphysic AI, a production house that recently added Digital Domain’s veteran VFX wizard Ed Ulbrich (Top Gun: Maverick, Black Panther) to its leadership team.

For many, this will be the first time they’ve heard of movie master Miller using AI to help tell his story. This, I believe, is how AI video will initially be integrated into most Hollywood productions. Piecemeal, imperceptibly, then gradually nearly everywhere. AI landscapes, cities, background actors, explosions, and in some cases, performance enhancements.

I’ve rarely heard anyone mention the AI used in the film to face match Anya Taylor-Joy to the younger version of her character, played by Alysa Browne. The AI work was handled by Metaphysic AI, a production house that recently added Digital Domain’s veteran VFX wizard Ed Ulbrich (Top Gun: Maverick, Black Panther) to its leadership team.

So, where does this leave all the humans? The reality is that there are already many traditional roles in filmmaking disappearing, from technical to support staff to even background actors. Whether the shift moves so broadly that the era of the human movie star eventually comes to an end is up to the aforementioned splintered audiences. James Cameron’s $5.24 billion Avatar franchise, despite the differing production methods, is a hint that audiences won’t necessarily shrink away from virtual worlds populated by AI actors if the storyteller is talented enough.

Nevertheless, I believe the reason there will always be “some” place for real video is the same reason Cruise insists on showing you that he’s doing his own stunts. An AI figure hanging from a plane isn’t “crazy.” It’s cool, at best. Having an actual human hang from an airplane in flight, just to tell us a story, is not only no longer necessary, it’s a bit insane. And that leap, that drama that reflexively makes you suck in your stomach because you know you’re watching a real human risk his life, is part of what Cruise is counting on to make what he’s doing special.

On a less perilous level, this is the same ethos that still leads AI startup founders to present themselves to the public—on company blogs, in CNBC interviews, on podcasts—as they tell their unique stories. Jobs was a storyteller. Ives helped Jobs tell his story, too. And even though Altman has the tools to tell his personal story via AI, he continues to tell his company’s story using his own body, even as all the Sora generative video credits he’ll ever need are at his disposal. Altman wants to capture the same human connection magic Ives helped Jobs deliver.

Viewers will evolve with AI video. More will come to accept partially and fully AI-generated movies. However, the human connection remains special, for now, when it comes to certain distinct messages. The imperfect texture of real people and places, whether a personal revelation, a founder’s business story, or a meaningful documentary film story, still holds meaning.

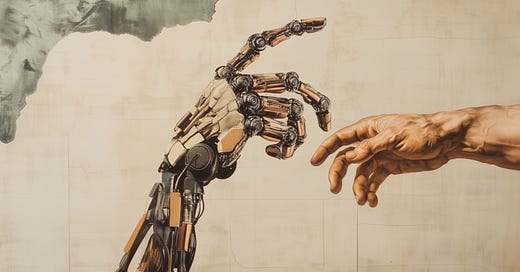

The real-world stakes inherent in our vulnerable onscreen moments are the last bit of spiritual fascia connecting us to one another as we tiptoe toward merging with the machines we’ve created. This final tenuous nexus of being is the wayfinder some traditional filmmakers, like Cruise, are looking to as their guide in the uncharted expanse of the AI video frontier.

In the meantime, like filters on an Instagram selfie, hybrid AI-meets-real video is about to make film and TV look a lot different, for better and for worse, depending on which filmmakers are lazy and which are inspired to take us to a new level of sensory wonder and exploration.